‘Perfumes are a bit like people – when they are too perfect, you don’t want to have dinner with them’

When Frédéric Malle first launched his company in the late ‘90s, the fragrance world was in a rut. “The entire industry was trying to create fragrances that would be sort of one-size-fits-all,” he says. “They would please every kind of individual and were more driven by image than by smell. [Brands] created first of all an image, then the packaging, and then the perfume had to be as broad-reaching as possible. And so in that context, noses were really sort of left behind and taken for granted.”

Malle grew up around ‘noses’, the industry term for a perfumer. His grandfather, Serge Heftler-Louiche, founded Parfums Christian Dior, and was succeeded by Malle’s mother, Marie Christine, as art director, making Malle a third-generation perfumer. “My mother used to take me to the office when she didn’t know what to do with me, so I spent a few Thursdays drawing at Dior [at the time, children in France had Thursdays off school],” he says. “I was pointed towards beautiful things, and I was told people smell good, or a flower was smelling of something. So from a very, very early age, I was drawn towards the world of scent.”

It is this experience and heritage that allowed Malle to see an opportunity in an industry that was becoming increasingly commercialised. “My idea was to make perfumes for their smell and not for image,” he says. It’s a concept that sounds logical today, thanks in no small part to Malle’s influence, but at the time it was radical.

Malle put noses front and centre by founding a publishing house for perfumers: Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle, leaning on relationships established during his time at prestigious perfume laboratory Roure Bertrand Dupont in Grasse. “The best perfumers in the industry were people I was close to because I’d been working with them for years,” he says. He gave them the means, guidance and freedom to develop original perfumes, then celebrated their talents by putting the creator’s name on the bottle. “[The idea was] to value them as artists, to show that they each have a different kind of writing, a different style.”

The process of developing a fragrance has remained much the same over the years, with Malle’s involvement being the only variable element. He admits it’s never particularly clear who has the initial idea for a new perfume, rather a constant conversation. “Either they come up with an idea, or I come up with an idea, but in fact they are so close that in all fairness, we never really know where the idea comes from,” he says.

The perfumer then creates a sort of ‘sketch’ of the scent, working with the raw materials “to see if we are talking the same language, and also to validate the idea to see if it’s worth suffering for or not.” From there, they begin to refine the concept, which can take up to a year.

It’s a delicate process, Malle says, as much about honing the formula as knowing when to stop. “The [goal] of those long months of fine-tuning is not to punish it too much, but to take the unwanted parts away,” he explains, adding that it’s about striking a balance between something “a bit sketchy” and absolute perfection. “Perfumes are a bit like people; when they are too perfect, you don’t want to have dinner with them.”

Malle does not believe in trends when it comes to perfume, more that there is a tendency for many in the industry to imitate the best sellers. He and his collaborators avoid this by sticking to three key rules: Following their instincts, staying timeless, and never following the prevailing trends. “Never use that background music that everybody uses because they are scared,” he says.

The result is a diverse offering of truly unique perfumes that, he believes, serves the consumer as an individual. “It gives our client the chance to choose a perfume that’s probably going to be very, very close to their personality instead of being like most brands the vision of one person, and it’s my way or the highway. It’s the opposite of that.”

There’s a saying in French that “shoemakers always wear the worst shoes,” but the analogy is not true of Malle, who has the pick of the Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle collection. “I think most of the men’s perfumes that we have are probably facets of my own style,” he says. He chooses perfumes according to the season or occasion, but his go-tos are Vetiver Extraordinaire and Geranium Pour Monsieur, both by Dominique Ropion, a celebrated perfumer with whom Malle has worked for over 25 years. His wife wears Ropion’s Portrait of a Lady.

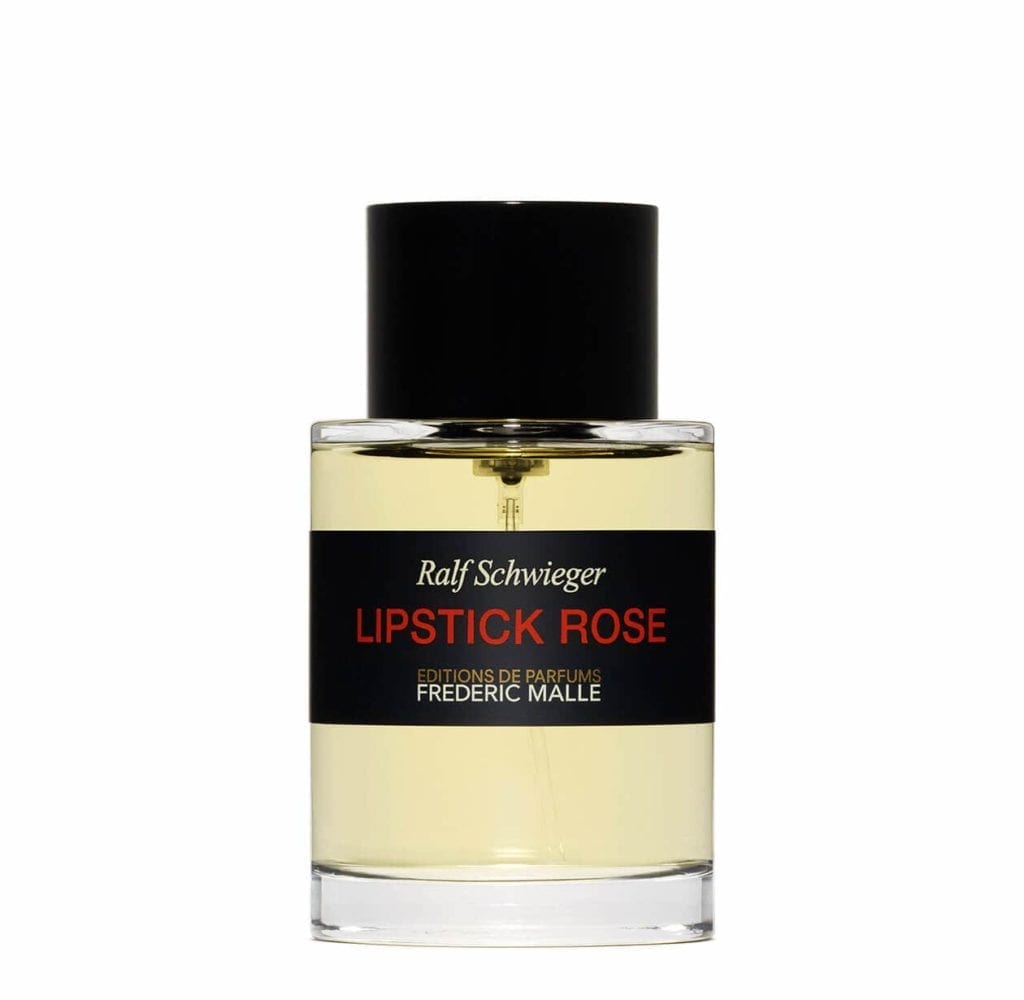

Malle is also a keen supporter of young talent, creating Sale Gosse with Fanny Bal, Ropion’s apprentice, and Lipstick Rose with Ralf Schwieger, who he scouted at a competition for young perfumers.

It is Le Parfum de Thérèse, though, that is arguably the most famous perfume in the Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle canon, created by the legendary late perfumer Edmond Roudnitska, who worked with Malle’s grandfather at Dior in the 1950s. Roudnitska created the fragrance for his wife Thérèse, and only Thérèse, to wear. After Roudnitska’s death in 1996, Thérèse entrusted the formula to Malle.

It’s hard for Malle to pick favourites though. “In hindsight, I suppose that I’m more proud of the ones that have been celebrated by the industry, or because they redefined a type of perfume,” he reflects. “But I must say that each time I launch a perfume, although I’m just there to hold the perfumer’s hand, I’m wholeheartedly for it and completely immersed in it. Some are more successful than others, but when I launch, I’m always proud.”

Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle is located at 14 Burlington Arcade. Learn more about the boutique here.